It's the Demography of Intelligence, Stupid. A Variety of Basic Facts on Why China is Beating the USA

by Sebastian Edinger

[This is the translation and comprehensive modification of a text that I published in German at the end of 2023. I have updated or supplemented the data where relevant; other data (especially demographic) have by and large not changed significantly in such a short time. Also, this essay was originally the third part of a trilogy on David Goldman’s work; hence the many references to his brilliant book You Will Be Assimilated. China’s Plan to Sino-Form the World]

Wherever you look—whether in politics or the media, in Germany or the USA—China is almost always catastrophically underestimated, even in circles where it is regarded as a legitimate geopolitical competitor to the United States. The still often-repeated phrase—sometimes as an objection, sometimes as an argument—that the Chinese are diligent and clever but not creative no longer stands up to real-world developments. Goldman, in particular, sees this very clearly and tries to help dreamers—those who stubbornly cling to phrases that shield them from reality—to face the facts. However, facing the facts also means, as a next step, combining demographic realities with findings from intelligence research. To my knowledge, Goldman has not done this, but it is necessary in order to place his arguments in a broader context and gain an even more comprehensive and realistic picture of the situation.

https://x.com/davidpgoldman/status/1563215722423078913

In the USA and Western Europe, it is no secret that today’s eighth graders—and even more so those in thirteen years—are no longer given such tasks. Since my focus is not on the internal decline of the West, but rather on the comparison with China, it is not relative figures such as fertility rates that matter here, but absolute numbers, which allow us to relate actual birth figures and intelligence potentials to one another.

Before engaging with Goldman, a few intelligence-demographic considerations should be outlined: Even though China is, de facto, in a difficult demographic situation due to a rapidly declining fertility rate, unexamined statistics can easily obscure the very real weight of absolute numbers, which provide a more reliable basis for comparison (general data). According to the South China Morning Post, 9.56 million children were born in China in 2022, compared to 3.89 million in the entire European Union (and in the years 2021 and 2022 combined, just about 8 million), and 3.66 million in the USA. Thus, in 2022, the EU and USA together had fewer than 8 million births. The significance of these absolute numbers increases even further when the IQ factor is taken into account: The average Chinese IQ (104) is higher than that of Western Europeans (about 100) and Americans (98). To avoid getting bogged down in distracting arguments about the exact IQ value of individual countries, I will, for the sake of argument, standardize the IQ value (thereby also sidestepping the unresolved question of the urban-rural IQ gap in China, for which there are still insufficient data; it is likely that intelligence in China is disproportionately concentrated in the major cities, which act as talent magnets but are almost demographically sterile). That is: With 1.6 million more births and a (conservatively estimated) average IQ of 104 (Lynn/Vanhanen give it as 105.8; see Lynn/Vanhanen 2012: 21), even assuming (counterfactually!) equal IQs, China would have an approximate (rounded) talent advantage in the following highly developmentally relevant IQ segments (for μ = 104, σ = 15—the standard deviation is also standardized here, since it differs slightly between Europeans and Asians):

IQ 125: + approximately 125,000 in favor of China (conservatively estimated)

IQ 130: + approximately 65,000 (gifted)

IQ 135: + approximately 30,000 (“1%ers” according to Western established criteria)

IQ 140: + approximately 13,000

IQ 145: + approximately 5,000

I leave it to those who believe in American fantasy IQs of 180 or 200 to calculate the numbers for higher IQ values.

In any case, China would have to become demographically much weaker and Europe and the USA much stronger before there would be parity in talent strength. However, this discrepancy is where Goldman’s 1973–1982 analogy fails: In 1973, the USA was demographically—in terms of TFR, but especially in terms of available talent—significantly stronger than it is today, when it finds itself in the midst of a functional South Africanization (Example 1: power supply, Example 2: transportation system, Example 3: calls for ethnocide). In 1970 (source), the basic configuration in a country that for a long time essentially consisted of two ethnic groups was: 87.7% Europeans/Whites, 11.1% African Americans; by 1983, it was: 83.1% Europeans/Whites, 11.7% African Americans. In 2020, we have: 61.6% Europeans/Whites, 12.4% African Americans, 6.2% Asians, 18.7% Latinos, and several other groups.

Whether one looks at IQ or SAT results (for example, for 2022: https://reports.collegeboard.org/media/pdf/2022-total-group-sat-suite-of-assessments-annual-report.pdf), the picture is essentially always the same (for a concise overview, see Murray 2021 and Rushton/Jensen: Thirty Years of Research on Race Differences in Cognitive Ability), and the fact that the tests (naturally) do not show perfect intercorrelation does not change the fact that their results, like those of cognitive tests in general, show a very high intercorrelation (the key term for further research is: positive manifold). China’s potential is incomparably greater than that of the USA and Europe combined, and nothing will change that for the better less than following the script of the abominable UN replacement migration paper.

It is striking that Goldman does not address any of this. Perhaps religious reasons stand in the way of opening Pandora’s box, but ultimately only Goldman himself can explain why he leaves out what he presumably knows and what should count as much as a hard fact as the economic or demographic data he cites.

But let us turn to Goldman’s important and highly recommended book on China, You Will Be Assimilated. China’s Plan to Sino-Form the World (2020), which today ought to bear the subtitle How China is Sino-Forming the World, and to the 2021 publication, available digitally, How America Can Lose the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

China's functional integration of foreign economies

In the introduction to You Will Be Assimilated, Goldman speaks with striking clarity: “I wrote this book because America’s response to China’s global ambitions is a failure. There are two big reasons for this failure. First, we chronically underestimate China’s capabilities and ambitions.” (Goldman 2020: XVII) Out of necessity, I will limit myself here to this aspect and will (for now) largely exclude both the internal problems of the USA and the military balance of power between the two countries.

At the center of Goldman’s analysis is Huawei, a company “with fifty thousand foreign employees and research centers in two dozen Western countries,” which he therefore describes as an “imperial company” (ibid.: XXXII). Huawei does not need to bring products from China to the West; rather, Huawei uses Western expertise to manufacture its Chinese-controlled products. These products are not primarily smartphones; rather, smartphones are merely an application medium for a 5G-based digital infrastructure, of which China is the undisputed pioneer and which extends across the entire so-called Fourth Industrial Revolution. Goldman picks up on this term (the expression was popularized by Klaus Schwab in 2016, but it does not originate with him and can already be found in the title of the VINT Research Report The Fourth Industrial Revolution from 2014; in fact, prophetically, a chapter in Claus Eurich’s 1988 book Die Megamaschine (The Mega Machine) already bears the heading “The Fourth Industrial Revolution,” by which he meant the computerization of society and the working world), which designates a revolution that extends to fields such as “robotics, the Internet of things, and massive big data applications to supply chain management, transportation, health care,” whose organization and design will be largely determined by the application of artificial intelligence. Goldman provides a detailed overview of the technological core areas on pages 3 and following of How America Can Lose the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

But why should everyone here make themselves dependent on China instead of pursuing their own path? At the time Goldman’s book was published, 21 European countries had already ordered 5G equipment from Huawei (cf. ibid.: 82), but under pressure from the USA, several European states joined the American sanctions and the boycott of Huawei, and they still continue to tolerate American pressure to this day. Yet, this alignment is unlikely to persist in the future, as:

China moves toward technological supremacy,

the US experiences a decline in global influence, and

US-Europe relations deteriorate further due to increasingly overbearing American demands, while China offers superior products.

Anyone who is tired of the slavish submissiveness of European governments can all the more laugh at the fact that Huawei has outmaneuvered the Americans and demonstrated that it possesses the intellectual and technological capacities to render such measures ineffective—while also developing an unparalleled capacity for technological self-sufficiency as a bonus. Even worse, the US is (for good reason) growing increasingly nervous about the quality of Huawei’s new Ascend chip. In response, it may now overreach by attempting to impose global export controls, which could backfire by pushing the world closer to China. Goldman saw this coming years ago and repeatedly warned that Huawei would achieve precisely what it is now demonstrating.

Source: https://twitter.com/davidpgoldman/status/1698537055284859207

How Europe will react when even the last skeptic finally acknowledges (since nothing happens here before that point) who is clearly winning the technological race remains to be seen. This also means: it remains to be seen whether Europe will choose China or the US as its master. So much for Europe. Others have already decided not to let their relationship with China be dictated by the USA: Mexico has allowed China to integrate itself into its own broadband infrastructure (cf. Goldman 2021: 10-11), as has Brazil, where Chinese AI optimizes entire soybean farms down to the smallest detail (cf. ibid.: 11). The effect? “‘Smart’ agriculture in Brazil and other large soy producers will rapidly reduce China’s dependency on imports from the United States and erode American exports at a moment when the US current account deficit is running at about $1 trillion a year.” (ibid.) As of now, approximately 70% of China’s soybean imports come from Brazil. The situation is likely to further deteriorate for the U.S., as China’s ties with Brazil are strengthening amid growing tensions with the United States.

“According to the Brazilian Ministry of Agriculture and Supply, total soybean production from the 2023/2024 harvest was 147 million tons and about 87 million tons were exported to China. For the 2025/2026 harvest, of the 165 million tons of soybeans that Brazil is expected to produce, 110 million tons are expected to be exported, of which China will take an important part, according to the Brazilian industry representative.” (https://en.people.cn/n3/2025/0521/c90000-20317734.html)But let’s get back to chips and technology in general. Is China offering gifts to friendly states, or are there dangers and risks here that are difficult to assess? In You Will Be Assimilated, Goldman discusses the possibility of backdoor implementations that are almost impossible to detect: “Even if data itself is protected by un-hackable cryptography, ‘backdoors’ hidden among the billions of transistors in a computer chip could be used by a bad actor to sabotage critical infrastructure.” (Goldman 2020: 87) In other words: With unrealistic optimism presupposing a benevolent application, one can indeed climb civilizational levels with the help of Chinese technology, but China can also shut off the lights and punish states back into pre-modernity at the push of a button if, from the Chinese perspective, someone behaves too inappropriately.

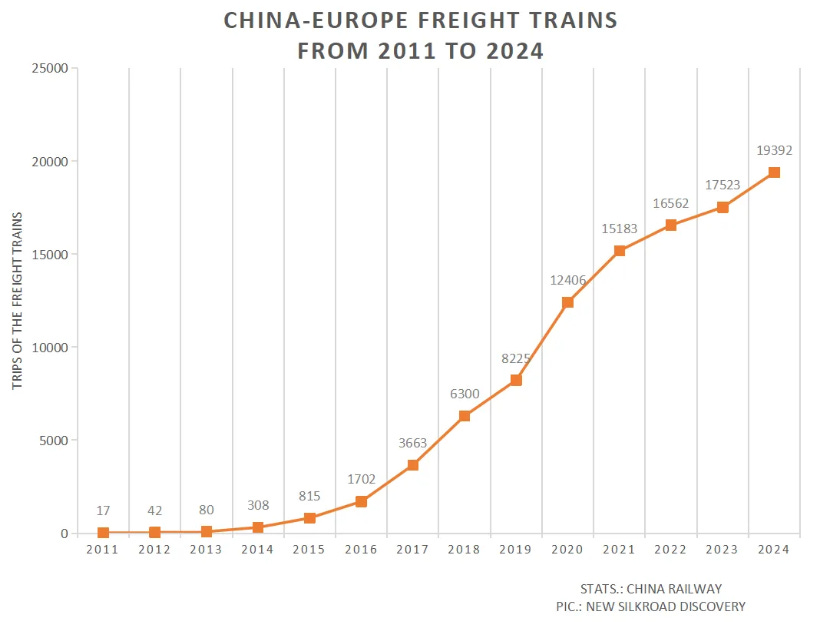

But why is what at first seems to be beneficial above all else actually a functional integration of foreign economies? Because China is able to provide advanced technologies preferentially to those countries from which it imports many goods, whose production is both quantitatively and qualitatively optimized by means of Chinese technology. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is the transportation infrastructure arm of this strategy, which Goldman aptly describes as follows: “Even more important are China’s inroads into the developing world. China’s $2 trillion Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), in combination with digital technology, aims to integrate billions of people in the developing world into China’s economic sphere.” (ibid.: 13) It does so by many measures, among them highly important infrastructure projects that have been finished since 2023, for example, the Jakarta-Bandung High-Speed Railway that connects China to Indonesia (travel time reduced from 3.5 hours to 45 minutes between Jakarta and Bandung), the China-Myanmar Crude Oil and Gas Pipeline (transports 22 million tons of crude oil and 12 billion cubic meters of natural gas per year while reducing China’s reliance on the Strait of Malacca for energy imports), or the Mombasa-Nairobi Railway (able to transport 1.5 million passengers and 5 million tons of freight per year with the journey time being reduced from 12 to 4.5 hours). Or just take a look at this impressive report: https://www.griffith.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/2093102/China-Belt-and-Road-Initiative-BRI-Investment-Report-2024.pdf. Also, China and Europe are getting connected closer and closer:

China’s strategy contains a key point that remains largely unnoticed by most people, which is why Goldman emphasizes it all the more: Unlike any other country, China can compensate for its demographic problems through the functional integration of other economies, because this integration includes young people from foreign and younger economies. While others must lament a shortage of skilled workers and are left hoping that technological developments will largely make up for it, China, through its technological monopoly and actual control over technological connection chains (analogous to supply and logistics chains), can bind and integrate foreign economies to itself so that the experience of dependency on China as subjugation from the Chinese side would only become apparent in cases of conflict. In general, China will, wherever possible and if acting wisely (not as in Sri Lanka, where a more debt-based colonial model was followed), aim for win-win situations that are attractive enough for the weaker, co-benefiting party to quash any questions of “Chinese colonization” from the outset; a good example is the soybean cultivation in Brazil discussed by Goldman, where Huawei’s 5G networks use 24/7 active sensors to “monitor” every single plant—that is, to check its condition and autonomously supply water, fertilizer, and pesticides as needed (cf. Goldman 2021: 11).

AI and humanoid robots

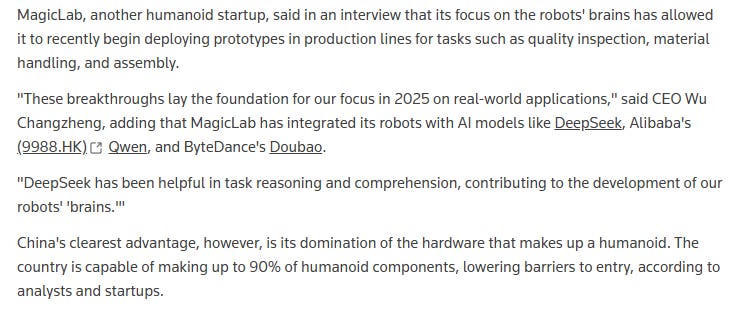

What Goldman could not yet concretely foresee in 2020 was the extent to which China would rival the US in the field of AI; there are good reasons to consider Chinese AI in certain respects superior to American AI in certain respects. However, Goldman also explicitly warned—in November 2024, months before the DeepSeek shock—about DeepSeek: “A Chinese firm to watch is DeepSeek, already the best LLM platform (according to ChatGPT!) for AI coding applications.” Not only is DeepSeek now widely recognized, but it is already—while remaining highly independent of non-national supply chains—embedded in the next step of Chinese AI development: the development of humanoid robots:

And while we in the West are still discussing the whole development under the label AI, in China experts are already talking about EAI, embodied artificial intelligence:

As explained in the Top Ten Trends in Humanoid Robots unveiled at the 2024 World Robot Conference in Beijing, embodied AI (EAI), also sometimes called “embedded AI”, is a high-performance intelligent system that can respond quickly and accurately under dynamic and unpredictable conditions. (https://www.china-briefing.com/news/chinese-humanoid-robot-market-opportunities/)The name to remember here is currently AgiBot, a company at the forefront of mass production and initial implementation of humanoid robots planned for 2025 (Xi Jinping visited its warehouse, highlighting its national significance). The warehouse houses around 100 humanoid robots and 200 human instructors, operating up to 17 hours daily, thereby producing 30,000 to 50,000 data points per day, supporting over 1,000 distinct tasks. In just two months, it generated over a million real-world data points, with tens of millions expected in the near future. Things are moving quickly: “We plan to open a second factory in Shanghai this year, and are aiming for an annual capacity of 10,000 units,” said Peng Zhihui, co-founder of AgiBot. An almost comprehensive implementation, transforming all areas of society, is targeted for 2027: “By 2027, MIIT [Ministry of Industry and Information Technology] calls for integrating humanoid robots into manufacturing supply chains, building an internationally competitive industrial environment, using them at scale, and expanding the use of humanoid robots throughout society.” (https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2024-10/Humanoid_Robots.pdf)

The fields of application are virtually unlimited. There is already close integration with the automotive industry (BYD), but it is only a matter of time before robots will be able to perform surgical procedures with unmatched precision. Above all, however, China will address its aging population with humanoid care robots, as the government has already emphasized (China to promote use of humanoid robots for elderly care). The opportunity this achievement presents is immense: what will be an identity-threatening demographic crisis for other countries will be reduced to an inconvenience for China. With care robots, the problems can be managed to such an extent that the country can wait for and patiently work towards a demographic recovery—most importantly, such a recovery will actually be possible. China will not have to transform itself through migration into an identityless human mishmash and cease to be China (the West doesn’t have to do this either; it’s just that for decades it has been governed by half-wits who are so stupid that you can even make them swallow brain-dead nonsense like the UN’s Replacement Migration document and turn them into pawns for the Swiss dysgenics agency).

AI and energy infrastructure

AI data centers consumed 4.4% of national electricity in 2023 in the US. This share is estimated to potentially rise to as much as 12% by 2030 (bear in mind that the estimates vary); the main energy burden falls on Virginia and Texas: “In 2023, about 80% of US data center load was concentrated in 15 states, led by Virginia and Texas.” Once consumption reaches 10% of total national demand, systemic risks (such as during extreme weather) are expected as early as 2028. In 2021, 75,000 miles were calculated as the minimum required for 2035: “Princeton University estimates that 75,000 miles of new high-voltage transmission lines—enough to stretch around the world three times—need to be built to reach that 2035 goal.” (https://eprijournal.com/epris-get-set-initiative-gets-going/) But what is the current situation? For 2023, the picture is as follows: “Construction of new high-voltage transmission in the U.S. has slowed to a trickle over the past decade, with only 55 new miles built in 2023.” (https://cleanenergygrid.org/fewer-new-miles-2024/) Even with a tenfold increase in speed to 550 miles per year, it would take 136 years to reach the target. Trump has implemented emergency measures to fast-track energy projects, but the gap between reality and necessity is absolutely gigantic. For medium-term modernization (by 2040), 6,800 new miles per year would be necessary. Small modular reactors and offshore wind farms are scheduled to go online from 2035, and HVDC (high-voltage direct current) lines will only become available in significant numbers from 2040. (Anyone who believes that solar energy is the solution here should bear in mind that its share of the national energy supply rose from 3% in 2020 to just 7% ; wind and solar generated “757 TWh of electricity in 2024”, while in China wind and solar rose “from 629 TWh in 2019 to 1,826 TWh in 2024”.)

The most optimistic data provided by Statista, those for 2021, don’t give reason for optimism:

What does this mean? The US will be overwhelmed by the additional energy consumption of the AI sector. At the same time, a reindustrialization is planned, which paradoxically is likely to lead to deindustrialization, as it requires energy that simply isn’t available in the necessary quantities. The more reindustrialization, the more rapidly energy scarcity will trigger an energy collapse. A large-scale relocation of, for example, European industry to the US cannot succeed, because the US simply cannot provide the required infrastructure. Do Europeans considering compliance with Trump’s call to join the US internal market even think about this problem? Probably not. The vicious circle looks like this:

factory projects → power shortages → production outages (brownouts, especially in Texas) → investment freeze → deindustrialization.

Much more could be said about this, but I must leave it at this hint, which already shows that these plans and announcements are more like blank checks than serious proposals.

But the intellectual potential for the necessary transformation is simply lacking.“Among energy sector employers, 71% struggle to find the skilled talent they need, according to Manpower.” (https://www.forbes.com/sites/corinnepost/2025/02/20/how-to-solve-the-energy-sectors-growing-skills-shortage/) Furthermore: “In the United States, 400,000 energy sector employees will hang up their hard hats within the next decade.” (https://www.greenrecruitmentcompany.com/blog/2025/03/powering-up-energy-security-burning-out-the-workforce) Anyone who thinks these numbers are too abstract and believes everything will be fine, and that enough talent will come along, should look at how things are going for TSMC in the US—even in an environment that is, in terms of intelligence demographics, comparatively favorable (especially compared to what can be expected in 2035). What is often omitted in the much-lauded showcase investment in Arizona is what measures TSMC has had to take just to remain operational: “TSMC’s decision to draft more than 1000 Taiwanese engineers to help stabilize the chip yields of its Arizona facility drew a torrent of criticism in America.” (https://english.cw.com.tw/article/article.action?id=3975) That was in 2023, but it wasn’t enough; in 2024 came this report: “TSMC, the world’s largest semiconductor manufacturer, has pushed back the planned 2024 start date of production at its Arizona factory by a year due to a shortage of skilled workers.” (https://qz.com/tsmc-blamed-a-lack-of-skilled-us-workers-for-delays-at-1850662936)

A few notes on several central topics of a more detailed comparison

All that has been said so far strengthens the assumption that China will be able to maintain its intellectual edge over the West in the long term. The key factor here will be demography—and specifically, the demography of intelligence. That China will have to remain largely homogeneous (over 92% of all Chinese are Han Chinese) is clear to the elites, who have undergone the rigorous Gaokao system and are not recruited in the same way as in the West, where no real elite selection exists anymore (it’s a binary choice: either elite selection or affirmative action; there’s no third way, despite rhetoric suggesting otherwise). Strategically, as Goldman shows, China is already clearly at an advantage, since AI development in China—apart from surveillance, which is hardly less pronounced in the West, though this is obscured by the fact that it occurs more subtly and with less overt brutality—is focused on functional optimization in core sectors and less on consumer entertainment.

However, the situation for the USA and the West is far worse in competitive terms than most people in the West likely realize. Therefore, in the following, I will attempt to provide an overview that is both comprehensive and concise of how the balance of power actually stands. The starting point for this account is the highly recommended December 2021 report from the Belfer Center, The Great Tech Rivalry: China vs. the U.S.; I will supplement this with more recent data.

Regarding quantum computers:

“China has already surpassed the U.S. in quantum communication and has rapidly narrowed America’s lead in quantum computing.” (p. 4) Just a few days ago, China presented the Origin Wukong, a new third-generation 72-qubit quantum computer, just after Google had boasted about being in the lead with a 70-qubit quantum computer. Angela Merkel celebrated a German 27-qubit quantum computer as a “technological marvel” in 2021 (Google already had a 54-qubit quantum computer in 2019). Who will dominate this field in the long term remains to be seen; moreover, who uses the technology in a smarter and more targeted way will probably be more important here than a mere metric performance.

Regarding artificial intelligence:

“China overtook the U.S. for overall AI citations,” according to the report. The relationship between quantity and quality, as well as the significance of the numbers, is disputed, but Caroline Wagner offers a noteworthy point in her article China now publishes more high-quality science than any other nation – should the US be worried?: “[I]n 2022, Chinese researchers published three times as many papers on artificial intelligence as U.S. researchers; in the top 1% most cited AI research, Chinese papers outnumbered U.S. papers by a 2-to-1 ratio. Similar patterns can be seen with China leading in the top 1% most cited papers in nanoscience, chemistry and transportation.” Data from 2023 further underscores the shift:

"According to recent reports, China leads the world in generative AI patents, having filed over 38,210 patents from 2014 to 2023. This figure is substantially higher than that of the United States, which recorded only 6,276 patents during the same period." (https://digitalstrategy-ai.com/2024/09/30/chinas-ai-strategy-into-2025/) The sector is larger in the U.S. and significantly more crowded due to a much higher number of players striving for the big breakthrough. However, this could also prove to be a weakness, as most of them will remain invisible before they disappear (or get bought up like Windsurf by OpenAI). It is by no means unlikely that a few Chinese giants will dominate the majority of the AI industry, and only those in the U.S. who can attract a critical mass from the pool of the top 2% will be able to survive. Furthermore, what remains crucial is what users will do with the models — in other words, how they will utilize them in practice. China is aiming to develop AI that is suited to being embedded in real work: https://cset.georgetown.edu/publication/china-2025-explainable-ai-project-guide/

The balance of power is clearly and continuously shifting because of the quality of input and output in the education system.

Regarding the state of education:

“China graduates four times as many bachelor’s students with STEM degrees and is on track to graduate twice as many STEM PhDs by 2025. By contrast, the number of domestic-born AI PhDs in the U.S. has not increased since 1990.” (The Great Tech Rivalry, p. 7) – Why is that? Who is surprised that the U.S., since 1990 and the demographic transformation that is slowly being completed, has not been able to increase the number of its doctoral degrees despite a ridiculous inflation of educational certificates? Take physics as an example: In 2018 and 2019, 93% of all physics doctorates (84% Europeans/Whites, 9% Asians) went to Europeans/Whites and Asians, who together accounted for about 65% of the population in 2019 (cf. Murray 2021). Since demography, when viewed as a factor in modern geopolitics, is fundamentally the demography of intelligence—no other factor carries comparable weight—there is, in the medium and especially in the long term, no real competition. But things get even worse:

China’s positional change within the global political economy has resulted in a continuous expansion in the scale of Chinese students returning home after their overseas studies. Since 2012, more than 80% of overseas Chinese students have opted to return - a big increase from about 5% in 1987 and 30.6% in 2007. (https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20241015145513146)Why must this horrify Americans? Because their domestic production of PhD holders is small, while “ethnically Chinese students accounted for about 18 percent of STEM graduates in the US” (https://www.nber.org/digest/202410/us-china-stem-researchers-and-students).

Regarding the education comparison:

Goldman points out a fact that allows the connection of the intelligence-demographic aspect with the cultural aspect of study choice: “Just 5 percent of our college students major in engineering, compared to one-third in China.” (Goldman 2020: XVII) The numerical fluctuations that appear here are negligible, so Goldman’s figures do not need to be disputed. In absolute numbers, to which I will return below in more detail and with concrete sources (as of 2016): 4.7 million STEM graduates on the Chinese side versus 568,000 on the American side. In addition: “Four out of five doctoral degrees in computer science and electrical engineering are awarded to foreign students, of whom Chinese are the largest contingent.” (Goldman 2020: XXII) The most recent direct comparative statistic available to me, which contains absolute numbers in an international comparison between global powers, is from 2016:

Source: https://www.statista.com/chart/7913/the-countries-with-the-most-stem-graduates/

What is remarkable is not only that China has about eight times as many graduates as the USA, but also that Russia, with less than half the population of the USA, has only a few thousand fewer graduates. How quantity and quality relate remains to be seen, but both Russia’s superiority in the military sphere and China’s coming dominance in several technological sectors can be considered a fact. Anyone who no longer wants to be fooled by clueless journalists, uneducated propagandists, or simply by Hollywood should read Andrei Martyanov’s 2019 book The (Real) Revolution in Military Affairs (and for those who want to see the results in a broader developmental context, also his 2018 book Losing Military Supremacy).

On biotechnology:

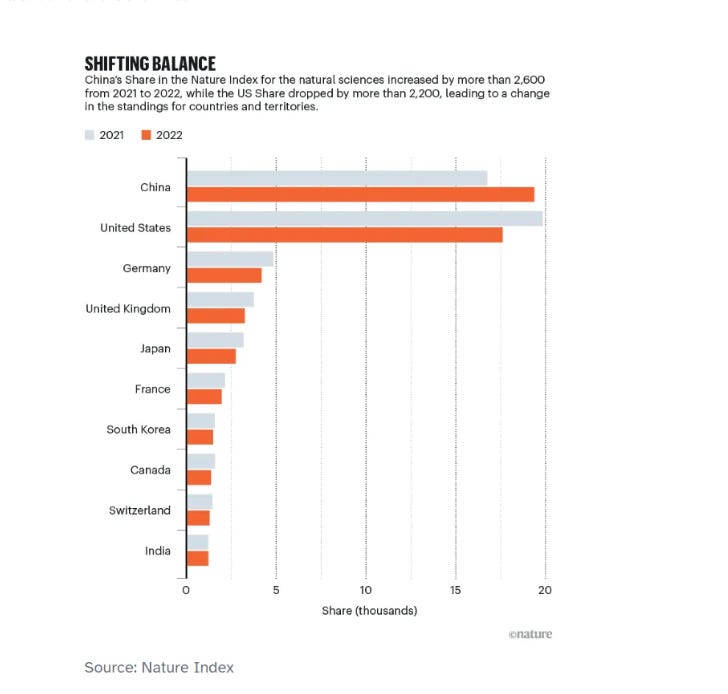

Regarding the field of biotechnology, the report tells us the following: “In 2019 and 2020, China overtook Germany and the U.K., respectively, and now ranks second in the Nature Index for high-quality life sciences research, increasing its annual output by 9% over the past year.” – However, this is now outdated; China is now in first place, as Nature informs us: “In 2022, for the first time, the country had the highest Share score in the Nature Index for the natural sciences, surpassing the United States.” What does the Share score measure? Well, this:

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-01868-3

And things are not getting better for the US (quite the opposite is true) when you take a look at recent data:

The institutional landscape is changing accordingly when it comes to rankings: http://en.ce.cn/Insight/202503/10/t20250310_39315213.shtml

Here we clearly see opposing developments that, when viewed from the perspective of intelligence research, align with demographic transformation. This process is not complete; the gap will continue to widen significantly in favor of China in the coming years. However, not all geopolitically central tipping points have been named yet.

On solar technology:

Data suggest the US is gaining ground here: “The United States has seen a 300% increase in capacity, now standing at 25 GW per year, thanks to incentives from the Inflation Reduction Act.” (https://www.pvknowhow.com/news/solar-module-capacity-global-manufacturing-2025/) Nevertheless, the reality is this: “China currently dominates the global solar module manufacturing market, accounting for 80% of the world’s capacity.” (Ibid.) What is to be expected? The following: “The world will almost completely rely on China for the supply of key building blocks for solar panel production through 2025. Based on manufacturing capacity under construction, China’s share of global polysilicon, ingot and wafer production will soon reach almost 95%.” (https://www.iea.org/reports/solar-pv-global-supply-chains/executive-summary) This speaks for itself and requires no further comment. Nevertheless, reference should be made to the excellent lecture by Keyu Jin, in which this is also discussed: Critical Issues Confronting China – Professor Keyu Jin – December 6, 2023 (on solar technology from 7:30).

On access to raw materials:

This is particularly sensitive: “And where China lacks resources domestically, it has secured them overseas. Chinese companies own 8 of the 14 largest cobalt mines in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (accounting for 30% of global output) and a 51% stake in the world’s largest lithium reserve (which, combined with other assets, makes China the largest producer of hard-rock lithium at over 50% of global production). Meanwhile, the U.S. imports 40% of its lithium, 80% of its cobalt, and 100% of its graphite.” (Grosch 2022: 31 f.) – But why is this so sensitive? Martin Grosch’s excellent book Geopolitische Machtspiele (Geopolitical Power Games) contains explanations on this (as well as on the entire global geopolitical situation), which could be considered so important that reading this book should be required for every high school student (not that this would necessarily have much effect), for example: “In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DR Congo), the main mineral mined is the tantalum ore coltan, which is found in virtually all mobile devices: More than 80 percent of the nearly 1,200 tons produced worldwide each year are extracted from the conflict-ridden region in eastern Congo and in Rwanda. Our entire high-tech industry depends on metals like tantalum.” (Ibid.: 58) According to Grosch, further deposits of these raw materials are also likely to exist in Tibet. Who, one wonders, has exclusive access here? (cf. ibid.: 138) What does this mean? Grosch is unequivocal: “So who will control the Heartland in the future? Certainly not the USA. The only question at present is how Beijing and Moscow will jointly or in a coordinated manner (e.g., in spheres of influence) control and dominate the Central Asian terrain.” (ibid.: 282) – Yes, China (above all!) and Russia; no, not Africa, as the unintentionally comical propaganda of uneducated, ludicrously over-credentialed, intelligence-demographic know-nothing experts would have us believe.

Remarks on the military balance of power

Since we are already discussing geopolitical circumstances, I would like to add a reference from another Belfer Center Report, which deals with the military balance of power (The Great Military Rivalry) between the USA and China. In the mass media, one may find all sorts of rhetoric about how the USA would defend Taiwan against China and that it is, after all, the leading military world power (which it is not). What result was reached in the very elaborate war-game simulations, which apparently were conducted repeatedly until a positive outcome was finally achieved? “[T]he most realistic war games the Pentagon has been able to design simulating war over Taiwan, the score is 18 to 0. And the 18 is not Team USA.” (p. 4) After quite honest efforts, they eventually gave up in frustration.

Another military note from the report: “China has more than 1,250 ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometers, while the U.S. fields only one type of conventional ground-launched ballistic missile with a range of 70 to 300 kilometers and no ground-launched cruise missiles.” (ibid., p. 12) The point here is that these Chinese missiles are high-precision weapons designed specifically for the defense of the coasts and coastal waters, and are capable of striking aircraft carriers with pinpoint accuracy and quickly and easily sinking them. The 18:0 defeat in the simulations is also due to the fact that Chinese weapons development has reached a stage where aircraft carriers are rapidly becoming obsolete assets (to put it more sharply: impressive-looking sea junk) and no longer have any decisive strategic use in the Pacific. Perhaps it would have been better to listen to Lee Kuan Yew when projecting one’s own military supremacy into eternity; in his 2000 book From the Third World to the First: The Singapore Story 1965–2000, Lee issued a prescient warning that now reads like a prophecy: “The United States may be able to stop China from using force for another 20 to 30 years. Within that time, China is likely to develop the military capability to control the straits. It may be wiser, before the military balance shifts to the mainland, to negotiate the terms for an eventual, not an immediate, reunification.” (Lee 2000: 570)

What does all this fundamentally mean? “[I]n the near future there is a ‘limited war’ over Taiwan or along China’s periphery, the U.S. would likely lose—or have to choose between losing and stepping up the escalation ladder to a wider war.” (The Great Military Rivalry, p. 2) – Anyone who does not know this is simply uninformed in this matter. Anyone who lies about it should be treated differently than a mere fool. Why a significant military gap will (necessarily) emerge between China and the USA can be found in the article US-China AI rivalry a tale of two talents, written by David Goldman and Handel Jones. Here are two key quotes:

(1) The China case:

“Chinese military and aerospace engineers have access to high-performance supercomputers and are working on the latest generation of technologies, with access to advanced semiconductor products. And after working with leading-edge technologies for the Chinese government, they will have their pick of jobs in the private sector.” (2) The (quite disturbing) USA case:

“Programming technologies within the military and aerospace AI projects were several generations behind the Silicon Valley standard, and Andrew had no interest in obsolete technology. In many cases, the software technology for new hardware is up to 20 years behind leaders in the US because the engineers that are already employed in the military and aerospace ecosystem are not skilled in the latest generation of AI technologies.”However, the comparison between the USA/the West and China is not limited to gradual differences on common ground, but also includes Chinese innovations of a qualitative nature that most Americans can scarcely imagine (and, to be honest, there’s an awful lot to say about this, but I just don’t see why I should be handing out tons of material I’ve accumulated and prepared—not simply compiled—on this for free, especially as I’m preparing a political consulting agency with someone). What we are looking at here is not only the qualitative difference in decision-making processes but the developmental gap between an ethno-state and radically meritocratic China and a childishly naïve, multiculturalism-obsessed, and deeply anti-meritocratic West. Here, as development in the West is moving in the opposite direction, we are witnessing the emergence of civilizational differences—not between China and the West, but between China and what will succeed the West in the former West.

Conclusion and Return to Goldman

In his lecture delivered at the National Conservatism Conference in 2021, David P. Goldman compared the current geopolitical situation of the USA in relation to China with that of 1973 in relation to the Soviet Union: in 1973, the Soviet Union was superior to the USA, but massive investments in education and research enabled the USA to clearly achieve military-technological supremacy by 1982. Goldman’s goal and programmatic guideline is a renewed “from 1973 to 1982.” In an essay published on January 17, 2024, entitled Seizing America’s Comparative Advantage, Goldman updated his diagnosis. What is the comparative advantage of the USA? The text contains a gloomy diagnosis but an optimistic prognosis:

“We will never catch up to China in raw numbers of STEM personnel. But our track record of innovation is unique in the world. […] The United States still has the opportunity to lead the world in technologies that haven’t yet been invented and new industries that no one has imagined. That is our comparative advantage.”

I beg to differ. Goldman overlooks several problems here. The USA not only has fewer STEM graduates, it is, as shown above, weaker than China in several core areas, and China is—Goldman explicitly mentions this in the text (as was already mentioned above but is also reiterated in this text by Goldman)—not bypassing American sanctions by buying up technologies on black markets but through its own innovations in virtually every area of technology.

But above all, Goldman, who sees all too clearly that China is about to outpace the West, overlooks something crucial: the demography of intelligence. There will not and cannot be another 1982, because there is no 1973. The demography of today’s USA does not allow for another 1982; more than that, it reliably rules out a new 1982 as a possibility. No clairvoyance is needed here, because the “genius of American innovative capacity”—if one wants to associate it with the work in Silicon Valley—is already dependent on Asian Americans (and their intelligence, discipline, and motivation) for about half, as Kenny Xu shows in his excellent book An Inconvenient Minority: The Harvard Admissions Case and the Attack on Asian American Excellence (exemplarily and suggestively: “In 2010, Asian Americans became a simple majority, 50.1 percent, of all tech workers in the Bay Area: software engineers, data engineers, programmers, systems analysts, admins, and developers,” Xu 2021: 137). This raises an important question: If the proportion of Asian—and, as Xu shows, predominantly ethnically Chinese—Americans is so enormous (in New York’s gifted schools, which were once 90% Jewish-dominated, they now make up 70% of students; cf. ibid.: 174), then isn’t this innovative capacity, under the right structural conditions, also adaptable by China?

This argument can be countered under the following assumption: There are qualitative differences in innovation capacity, and the innovations of recent decades are less fundamental, whereas the true genius was that of the 20th century, which after 1945 was dominated by Americans in STEM. In that case, this genius would have an ethnic basis, but the problem would still shift in a rather discouraging way, because it can very well be argued that the innovations of recent decades are primarily novel combinations or highly refined advancements of essentially pre-existing ideas (for example, the smartphone integrates functions that previously existed independently of the smartphone; solar technology, for example, is not based on any theoretical or fundamental scientific discoveries that were not already well-established in the 20th century). In other words, from this perspective, we live in the “age of implementation,” in which—to China’s advantage—the quality of available intelligence and the coordinated exploitation of its potential take on even greater importance compared to genius tied to individuals; there are no longer innovations like quantum theory or the theory of relativity in the 20th century, but innovation mainly means that someone, usually research groups, was able to realize something that had been widely anticipated; innovation primarily means implementation—and learning how to implement what you know can be done. This issue of dependency on advanced software and colleagues within research groups furthermore applies to every genius, whether American or Chinese; as Matt Clancy demonstrates in his insightful essay Science is getting harder. The year 1970 marks a decisive breaking point, ironically in the humanities as well as in the natural sciences.

This situation is by no means external to what Goldman calls the “American genius,” as long as one does not want to mystify it, because what has already been invented does not need to be invented again—that is, the genius of American innovative capacity faces historically (as well as politically, culturally, technologically)—a completely different situation with new tasks that bring entirely different demands. The fact that the USA was able to dominate the 20th century does not imply that, even under hypothetically similar demographic conditions, it would be capable of similar achievements in the 21st century. The objective state of science and technology severely limits genuine innovation capacity, as the aforementioned essay by Matt Clancy clearly demonstrates. “Innovation” is not, as Goldman’s invocation of American genius suggests, a purely intrinsic quality, but to a significant extent also a situational one. Innovation capacity, both quantitative and qualitative, cannot simply be squeezed out of the essence of the American spirit when it comes to entirely different innovations in a completely different competitive environment, at a completely different level of complexity and intellectual challenge, with a completely different demography.

And since we are already discussing sociocultural prerequisites in their historical specificity: The US has abandoned meritocracy or even declared war on it (and even if you want to change this now, it will first take time for changes to take effect, and second, the damaging effects of social media and the nonstop internet need to be tackled). There was no American genius and DEI, and the relationship between DEI and genius is an either-or situation. DEI is the structural and substantive anti-genius initiative par excellence, the institutionalization of the undermining of meritocratic principles. To turn the anti-Chinese clichés here against the USA: DEI is much more efficient in producing an ant colony than any harsh meritocracy, and if one accepts the premise, unlike Chinese homogenization, one of uniform talentlessness or mediocrity through talent suppression and conditioning to endlessly bark what can be taught to an 8-year-old in 10 minutes (while having the temerity to call it “theory”). When such groups simultaneously seek to take over all relevant power positions in society, it is clear that power is desired, but selection according to meritocratic principles must be the mortal enemy of those power-hungry individuals who rally on an identity-political basis. In the long run, DEI necessarily produces a de- or un-modernization (Victor Davis Hanson uses the term “de-civilization”). But how meritocracy is to be reinstalled at all, after the hedonistic-infantile “give me, give me, give me” attitude almost completely determines the motivational structure of today’s influential groups, is the great open question.

A hard and thorough re-meritocratization of the education system—not only in the USA, but throughout the West—intended to reestablish it as an axiologically transformative and mentality-shaping societal force, could only have the necessary (intelligence-demographic) transformative effect in the long term and over several generations. As things stand, I am—unlike Goldman—convinced of the following: China’s victory will also be the victory of homogeneity over heterogeneity, the latter not becoming anything better simply by being called diversity. China’s victory will also be the symbolic victory of the Gaokao over the tolerance of spreading illiteracy and the abolition of those standards whose binding force alone allowed the West to rise from pre-civilizational insignificance to what it was a few decades ago. The effective abolition of universities and the hollowing out of qualifications that regulate university access is not an isolated phenomenon: Accordingly, the standards for “partner choice” are also changing, which (in Germany, too) have taken on almost jungle-like characteristics since the early 1990s to a fundamentally destabilizing extent, leading to an increase in out-of-wedlock births resulting from merely temporary liaisons based not on shared origin but on pre-personal states of desire. At so-called universities, people teach and learn with the same level of rigor and refinement that is at play when they cluelessly marry, soon divorce, and generally copulate in the orientation nirvana of societal decay; with the university as an axiological societal model with strong radiance, the family and the principle of hypergamy are being buried.

I am aware that China faces many and sometimes dramatic internal problems, but the question is who the opponent is, and they—the West’s self-destruction has gone too far—will probably leave this opponent far behind, for the West has, with the “educational trinity” (Karl Löwith) of the beautiful, the true, and the good, abandoned the will to live in its civilizational or high-cultural form. China, on the other hand, has the Gaokao, the universities that are part of the 985 Project, and meritocracy as an axiologically society-defining principle—the USA is plagued by spreading illiteracy (Example 1: “In 26 school districts, no low-income third-grade students were proficient in reading.”; Example 2: “Not a single fifth grader at Martin Luther King Jr. School, in the shadow of the Fruit Belt neighborhood, tested at a proficient reading level in 2022.”; Example 3: “Last year, almost 60% of California’s third-graders, the students most deeply impacted by distance learning and other Covid disruptions, could not read at grade level.”; Example 4 and Example 5, relating to African Americans in the USA; the state of Oregon has already capitulated—anyone who wishes can easily find dozens more such examples), which one must grasp in numbers only to still not believe what is the case. Last but not least, China values the achievements of the West far more than the West itself does (see Chang Che’s China Looks to the Western Classics or Han Feizi’s Open Letter to Chinese American High School Students—Goldman has pointed to both texts on X); hardly anyone has understood this more clearly than David P. Goldman, as his essay Western Civilization, Chinese Style demonstrates.

References:

Goldman, David P. (2020): You Will Be Assimilated. China’s Plan to Sino-Form the World. New York: Post Hill Press.

Grosch, Martin (2022): Geopolitische Machtspiele. Wie China, Russland und die USA sich in Stellung bringen und Europa immer stärker ins Abseits gerät. [Geopolitical power plays: How China, Russia, and the USA are positioning themselves and Europe is increasingly being pushed to the sidelines] Reinbek: Lau Verlag.

Lee, Kuan Yew (2000): From the Third World to the First: The Singapore Story 1965–2000. New York: HarperCollins.

Lynn, Richard/Vanhanen, Tatu (2012): Intelligence. A Unifying Construct for the Social Sciences. London: Ulster Institute for Social Research.

Martyanov, Andrei (2018): Losing Military Supremacy. Atlanta, GA: Clarity Press.

Martyanov, Andrei (2019): The (Real) Revolution in Military Affairs. Atlanta, GA: Clarity Press.

Murray, Charles (2021): Facing Reality. Two Truths about Race in America. New York; London: Encounter.

Xu, Kenny (2021): An Inconvenient Minority. The Attack on Asian American Excellence and the Fight for Meritocracy. New York: Diversion.